p.32. The observation that Roger was always searching for the perfect studio is very true, and he said as much to me, at Newlyn in 1958. Indeed, this led to me finding a studio for him (when he was living with us at the Newlyn Art Gallery). This was the studio at Tom Barnes’ house, above the old harbour. The room was rather dark and bare, but it had a splendid view across the harbour, northwards. Subsequently, a large Hilton painting was discovered, keeping the rain out (I think) in the roof of the building, but this was after Roger was dead.

Contrary to general opinion, Roger was a perfect guest when he was with us. He was interesting, entertaining, and when not outrageously drunk, very humorous. He gave me good advice with my own work, advice founded on the dicts of Bissière whom he still quoted with approval.

Tom Barnes was not the ideal companion for Roger, being a noted drunk, and although Roger enjoyed his company initially, I think he later found him a bit of a bore, as conversation was limited. Barnes used to look after my small fishing boat for me, so I knew him well, and I know that Roger made quite an impression on him.

Both Karl Weschke and Sydney Graham used to come to our flat under the gallery, to converse with Roger, but these meetings usually disintegrated before the evening was out. On one occasion, Hilton accused Weschke of having “hands stained by the blood of a thousand Jews” – but both then fell about laughing, and Roger exclaimed in his characteristic way – “But that’s ridiculous!”. However, this was the only occasion on which I recall Roger hinting at his Jewish ancestry.

Sydney and Roger were much given to drawing on the table on odd scraps of paper, embellishing each other’s work – valuable now I suppose, but they were just thrown away. Sydney was also prone to compose on the spur of the moment, and I still have a short poem he wrote about us and our young son which was quite haunting.

It must have been in 1958 that Roger told me he was writing a statement, for a catalogue, I think, or a letter to [American art critic Clement] Greenberg, and was having terrible trouble with it – “But I’m not going to show you,” he said, “because there is nobody who would understand what it is about. It is way ahead of their thinking.” About this time, he took me to see the new paintings. These were on large sheets of hardboard as I recall, and probably the pictures that he subsequently regretted showing anyone; “You won’t understand them anyway,” he said, but seemed interested in my reaction to them. They were, as far as I can remember, the first Hiltons that I ever saw with figurative references in them. After this he expressed interest in some small wooden panels that I had been given by the Marquise de Verdières Bodilly, the daughter of T. C. Gotch (panels that I subsequently discovered in 1989 were still being sold in Zecchi’s artists’ colourman’s shop in Firenze). I gave him a number, and he painted a series of small works, with figurative references again, and I am under the impression that they were shown at the ICA [note 1], when it was in Dover Street – in fact, I seem to recall seeing them there. I think that one, very similar, is reproduced in colour on p.7 (No. 11) in a Belgrave Gallery catalogue of March 1990 (“Some of the Moderns”), but dated 1966, possibly erroneously. Could this possibly be a picture I saw at the old Arnolfini Gallery on the Triangle in Bristol, in a Hilton show around 1967, and much coveted?

When visiting Roger at The Abbey on one occasion (where he lived in the incredible company of aged gentlefolk such as Mrs Horsefall, and ex-clergyman’s wife), he told me to go and have a look at the drawings he’d been doing, and if I liked them, to help myself. These suggestive nudes, in conté on small sheets of paper from a (Woolworth’s, I think) pad of paper, were scattered across his bed, where he had obviously been drawing. I still have four, although the white paper, being of poor quality, is now brown.

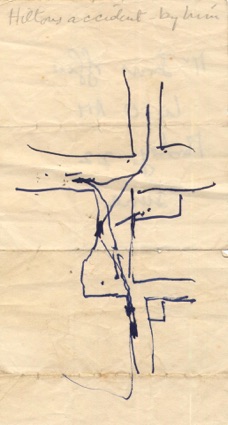

I cannot date another drawing that I kept, a somewhat bizarre one but still very Hiltonish, showing the route of his car (possibly Land-Rover), in an accident in Penzance. He did this for me in the sleeping compartment of the night train to Paddington from Penzance, when we were journeying together. I have a feeling that he lost his licence as a result of this accident.

You perhaps have not seen a Hilton Christmas card that I received, having unwisely sent him one first. This work in gouache and charcoal, dated 1974, is very gay, and says – “Christianity Stinks. No ass, no dove. There is no God. No Virgin birth. Nothing. Alls foolish.” (I should have known better.)

I can’t now recall what I wrote to you in a previous Hilton letter, but am sure I told you how he protested, when I was driving him to Zennor on one occasion, “Stop pointing out views to me, Canney! I hate views!!! You’re just like Heron – he’s always wanting to show me views.”

Hilton tales are of course endless, so I won’t go on, but I have to admit that I can’t recall any specific remarks by him about children’s art, and only one about figuration, in which he said that he had nothing against it, but it had to be arrived at, via a previous apprenticeship in abstraction. One couldn’t hope to arrive at any worthwhile figuration if one proceeded from traditional figuration as a starting point. I can’t remember the exact words, but this was the gist of the argument. I think he suggested this in 1958 when he was trying to arrive at some satisfactory solution to the problem himself.

The Watkiss tape in which he says that “children are realists and artists are not” is interesting, and he admits there that one can learn a lot from children’s art. However, the early sketchbooks, and the horse and cart on p.25 of your catalogue (Cat 115D) show that the subject matter of the last gouaches, which were certainly child-like, had been with him for a long time. When I went up into the studio, just after he died, there was a beautiful small Matisse cut-out book with horses, I think, and he treasured that, Rose said. I also think that his passing remark about [Henri] Laurens in the Watkiss tape is a vital key to his late drawings. Some Laurens drawings are so like Roger’s, or Roger’s are so like them, that one can hardly believe it. He was obviously a major influence. (See Laurens’ illustration p.125 in “Libri Cubisti” by Stein, publ. La Casa Usher. 1988).

Thinking back to my early years when I was “serving time” as principal art master in a London secondary modern, the direct and spontaneous way in which the children used to paint reminds me of the spontaneity of Roger’s work. I used to watch with amazement, as the children would proceed on paper with absolute certainty and with no attempts to change or erase the image. Roger says, “Never erase, make something of your mistakes,” and this is what they used to do.

The directness in his relationship with others, which took most people aback, was obviously how he painted and drew – although he told me he spent a lot of time looking and thinking, before acting spontaneously. There was also that technique of his, of having the picture around until he knew intuitively and exactly what he had to do with it – and that was possibly merely making a single mark to complete the work. The children were, of course, in more of a hurry to get on with the picture, but the directness was the same. The pictorial idea seemed to appear immediately at the end of the brush or pencil – no hesitation, and certainly the late Hiltons look like this as well.

A few weeks before he died, I was in his room, looking through the stacks of gouaches that were beside his bed, and at the miniature gallery of works that Rose had pinned around the walls, so that he could see what he’d been doing. The sheer energy, the outpouring, the colour, and the carefree nature of the images, greatly impressed me – whilst Roger conversed remarkably cheerfully considering his truly parlous condition. I found it impossible to relate this human wreck with these optimistic paintings, and I asked him, how he could possibly produce such cheerful work under these circumstances. I can’t remember the exact words, but with a dismissive gesture he said – “There’s nothing else left – what else have I got?” Rose said he was singing childhood nursery rhymes and songs before he died, including, “Daddy wouldn’t buy me a bow-wow”. The last gouaches have something of this innocence about them.

Note 1: Was this possibly the ICA show of paintings 1953-7 shown in Feb. and March 1958?

Note 2: The date in your catalogue footnotes for the renting of the Newlyn studio as 12/8/58 seems right to me, although my diary of that date was left in the UK I think, so I can’t check it. However, Roger was in Newlyn well before that – Christmas 1956 perhaps, as I recall him in the Tolcarne Inn in a (black?) raincoat and cap, winter-wear, and with a peaked cap, looking sharp, aggressive, and rather London-ish. Lanyon was there and said to me – “He will liven things up a bit here – really good painter”. Denis Mitchell, Frost, and possibly Heron were also there.

PS: Roger and I shared a certain common ground, in that Ruth’s father was a clergyman, as was mine; we both made a disaster of our OCTU officer training courses, being mutually unsuited to command; and I entered the army at about the same time as Roger was captured at Dieppe. The coincidence of those dates seemed to give him some kind of satisfaction – “You’re just a young fellah Canney”, and that sort of thing. The blimpish speech is well noted by Ruth in your catalogue. He was really quite upper class and formidable when he wished, rather senior-commonroom intellectual in manner, with that dry and pedantic voice that warned one never to make a casual or careless statement. “What d’you mean?” he would say, and one can hear it in the Watkiss tape. Trouble lay ahead!

Have you ever approached Bernard Cohen, as Nathan, his son, said his father was teaching at the Central with Roger, and said he always got on well with him, but after eleven in the morning, there was no possibility of rational conversation? Karl Weschke knew him well and spent a lot of time in argument and discussion with Roger, but I imagine you have checked that source long ago.

I was interested to see in your catalogue that Ruth ascribes Roger’s drinking to painting problems, and dates it as beginning around the time of Matthew’s birth in August 1948, much earlier than Heron maintains. He seemed to think it started in Cornwall. I was never convinced by this. Nor have I ever been convinced by Patrick’s story, that Roger was originally timid and quiet, saying nothing when he first met him in London. If provoked he would never have been the shrinking violet.

Regarding Roger’s reaction to American Art, I met him at the 1956 “Modern Art in the United States” show at the Tate when I was there with Peter Lanyon. Roger was rather dismissive of the art – “They’re doing nothing different,” he said. “It’s just bigger”, but I got the impression that he was actually taking it seriously. I met him again at the “New American Painting” show at the Tate in March 1959, and went around the exhibition with him. I think he felt there was too much “staining”. At a subsequent Tate show – (was it the Dunn International?), which I visited with Lanyon, Roger was transfixed by an Ellsworth Kelly, a giant ballooning form – a two coloured painting as I recall. “I think,” he said, with his characteristic cackle, “that there’s not enough there for me!”

After Roger’s disastrous intervention at the John Moore’s banquet in Liverpool, at which Councillor Braddock collapsed and died, he went into hiding. He was being pursued by the press for some time. Meeting at the Tate once more, we agreed to go to the opening of the new Grosvenor Gallery (I think it was), later in the evening. I endeavoured to dodge the issue, but was unfortunately intercepted by Roger in a nearby pub and so, as his “cover”, had to attend the opening – he being the “persona non grata” at any public occasion. After he had insulted Mark Glazebrook’s fiancée and shouted at David Hockney across the crowded gallery, I finally escaped, only to see Roger being ejected into the street. Life was never dull when Roger was around.

A mutual respect existed between Hilton and Scott and both spoke frequently about contemporary French art. In his humorous way, Hilton would praise Mary Scott “ “Damned good wife – does all his business for him – looks after things. I need a wife like that.”

Both artists had, of course, worked in France, but Scott had been to the USA as well, and met the leading American painters early on, which Roger hadn’t (I think).

A concern with the “painterly” in art was common to both artists, and the use of white on white, and black on black occurs in the paintings of both. When Scott used to ask me, “Do your students know how many whites there are, and the difference between them?” this question had a Hiltonian ring about it; but there is also an indication of the order that exists in Scott’s painting, whereas Hilton’s was essentially disordered, anarchic, and spontaneous, although we know he accepted “the rule that disciplines the emotion” – in this case the rule of Bissière and the School of Paris.

ROGER HILTON (2): Introduction to “The Night Letters” >